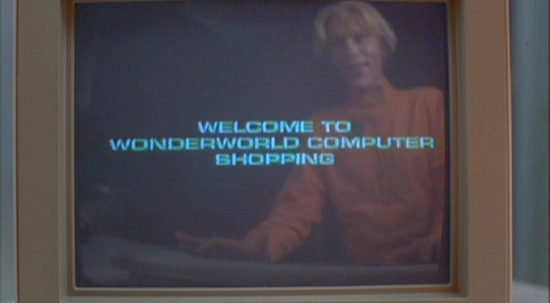

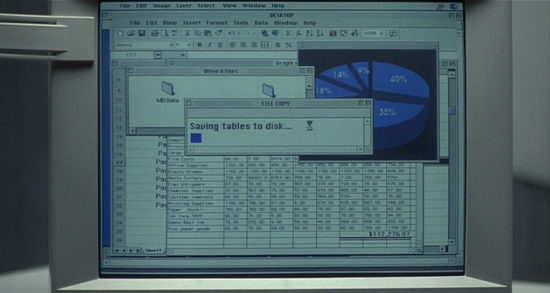

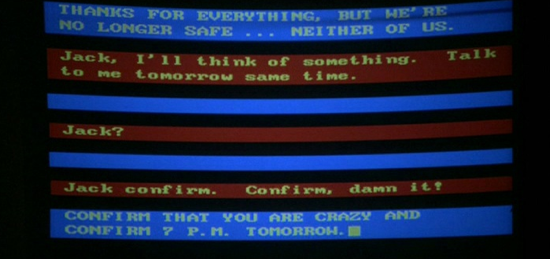

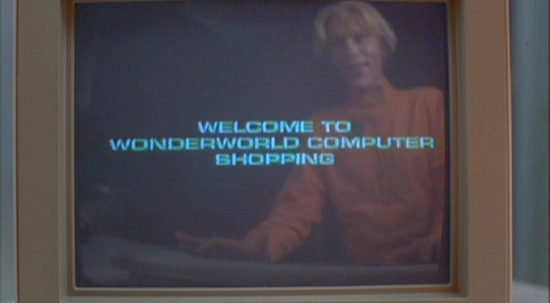

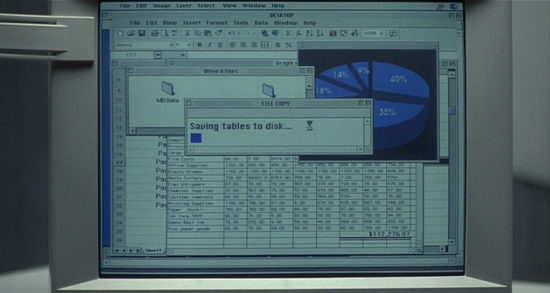

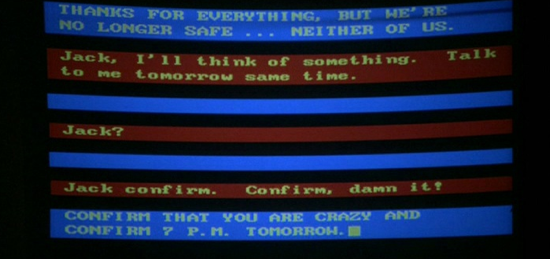

Recently, a site started making the rounds called Kit FUI — a new IMDB-like database of FUIs, fantasy or fictional UIs from TV and film. You know the ones: the virtual-reality Unix filesystem from Jurassic Park, the Terminator 2 HUD, the Esper photo analyzer from Blade Runner, and countless others.

Of course, Kit FUI wasn't the first site to track fake UIs. In 2007, Starring the Computer began indexing computers in film, many with fictional displays. Access Main Computer File started on Tumblr in 2010, and Fake UI followed in 2012.

I've linked to every one of these sites in the past, because each reminded me of an incomplete project I started in 2004, but always wished I'd finished.

In August 2004, I posted a question on Ask Metafilter asking, "Is there a website compiling framegrabs of computer screens in feature films?" The consensus was no, so I decided to do it myself.

One Metafilter member, Mike Lietz, responded that he was willing to capture some screenshots from his own DVD collection. We connected by email and got to work.

For lack of a better name, I called it "Screens on Screen" and set up the database and a simple viewer, while Mike started sending me screenshots. I built a tool for categorizing the UIs by period (past, present, or future), the platform, and what type of application they depicted. But the data entry was tedious, and Upcoming.org was starting to take off, so I put it aside. But not before Mike had captured over 1,200 screenshots from 47 films, dumped into an open directory on my server, where it stayed undiscovered for nine years.

Yesterday, on a whim, I mentioned my secret stash of screenshots on Twitter.

It immediately exploded. Even with its extremely simple directory listing, it captured people's imaginations.

Within a couple hours, three awesome geeks immediately built new ways to browse the collection.

And me? I'm absolutely giddy that people are finding new uses for a project that sat on my server ignored for nearly a decade.

Any creative person builds up a cache of unfinished projects. They usually stay hidden forever, buried and unexplored, taken to the grave.

Photographer David Friedman constantly came up with ideas he didn't have the time to pursue, so finally decided to start doing idea dumps, posting his work in its incomplete state. To his delight, several of his ideas were picked up by his readers, who went on to make them real. I shouldn't have been surprised the same thing would happen with Screens on Screen.

I'm going to take this as a personal lesson: stop hiding your imperfect and incomplete ideas for years. Stop collecting them in your head, like dying butterflies in a glass jar. It's always better to let them fly.